Smart mouthguards help high-school football coaches make safe decisions from the sidelines

No athlete likes being benched, even temporarily.

Practices and games help players get better and achieve the guts and glory under Friday night lights. But when high school football athletic trainer Craig Olejniczak sees one of his players take a hit approaching 90 g-forces, he advises the coach to take him out for further evaluation. It’s a tough call, but one that can prolong a competitive career.

Olejniczak is the athletic trainer for Middletown High School in New York, where he monitors every player using Vector mouthguards and software created by i1Biometrics, a company based at the other end of the country – in Kirkland, Washington, just east of Seattle. Sensors embedded in the mouthguards collect data on every hit and tackle his varsity football players absorb, and allow him to make decisions that help protect them.

“High school players are getting the most impact from coachable moments during these developmental years,” says Jesse Harper, the CEO of i1Biometrics. “They’re still learning and haven’t formed bad habits yet. Coaches play a big role in teaching. They mitigate long-term risk. The younger we can expose the athlete to coachable moments to correct their technique, the more it can lengthen their careers.”

Heightened public awareness about concussions among youth football players has helped fuel the appeal of mouthguards to coaches and athletic staff. Harper’s company estimates there are 1.6 to 1.8 million sports-related concussions in the United States each year, and a study published in the Journal of Athletic Training revealed that concussions represented 8.9 percent of all high school athletic injuries, with the highest rates in football and soccer.

Another study showed “the average high school player is nearly twice as likely to suffer a brain injury as a college player.” In 2009, emergency rooms reported a quarter of a million concussions for those under age 19. In 2001, that figure was 150,000.

“You can’t turn on a TV without hearing about concussions in football,” Harper says. “Athletes are much bigger and faster, so there’s potential for more. We have a chance to really understand what a concussion is and what leads to it.”

The mouthguard sensors incorporate ESP Chip Technology, which measures the linear and rotational accelerations of head impacts during practices and games. An accelerometer and a gyroscope deliver data from which can be extrapolated the severity of impact and where it came from. Team trainers and coaches work off a dashboard that shows the live feed.

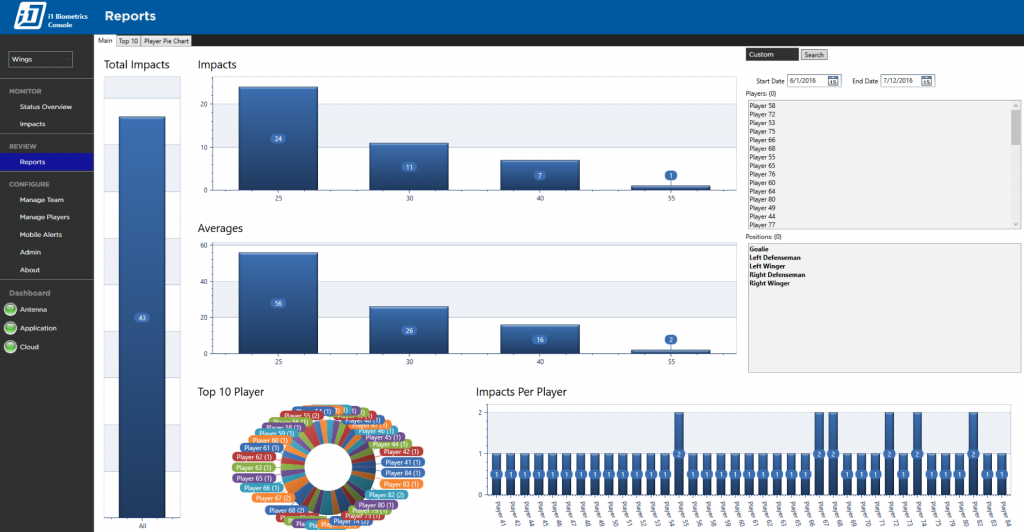

The sensors in the mouthguard collect data and store it on the device, then the software analyzes the data, which trainers and coaches use to create actionable plans to help players avoid future injuries. It alerts users that a large impact has occurred, and they’re able to see a 3D rendering of where a player took that hit and overlay it onto a heat map.

This translates into real-time data that coaches can use to make immediate play changes, including removing players who have been hit hard enough to trigger thresholds set by the team, resulting in flagged alerts that can be pushed to mobile devices, too. Teams can also tailor those thresholds to individual players, based on their history and any health issues that need monitoring.

“There’s a pretty compelling draw for the technology, especially for people who have children in football,” says Ray Rhodes, one of i1Biometric’s founders responsible for product development, and whose own son was a high school football player.

“There’s always going to be impact. There’s never going to be a perfect helmet, though they’re getting better. The effects of concussions are cumulative – there really should be a history – so our feeling was that we should be tracking the exposure to athletes from the beginning of their careers. The reason we chose mouthguards is that they’re directly coupled to the skull, so we get a very accurate representation of what the head is experiencing.”

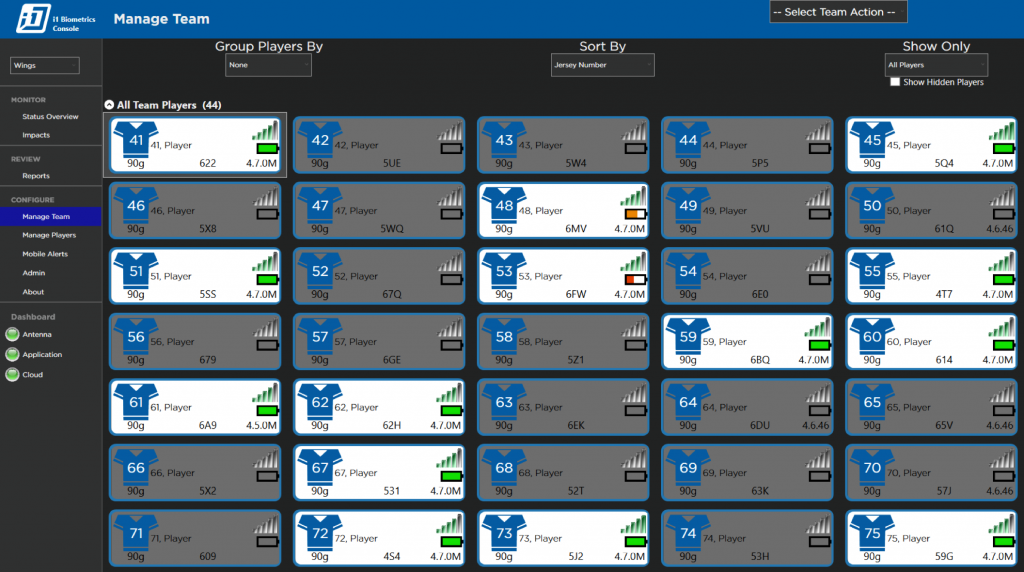

The data from the mouthguard sensors feed into the i1 Biometrics Data Analytics Platform, a tool for athletic trainers and sports medicine personnel that helps them make more informed decisions on the field. Data is transmitted in real time to a laptop or tablet at the sideline, since many practice fields or indoor stadiums don’t have internet access.

The information is stored on a local SQL database, and as soon as the coaching staff has an internet connection, that information syncs to a secure cloud environment powered by Microsoft Azure. The software is written for Windows 8 and 10, and while some schools use Surface tablets, most use PCs and laptops.

“We were originally on Amazon but we switched to Azure,” Harper says. “[Microsoft] has been a fantastic partner, geographically close and very responsive. That’s important, how we work together. We are trying to figure things out to push the envelope in a nascent category.”

As summer winds down, young football players across the country have already returned to their schools, ahead of their classmates, to practice for the upcoming season.

Middletown High School was the first U.S. high school to beta test the mouthguards in 2013, as part of a pilot program. Now, approximately 60 teams (6,000 athletes) use the Vector. Middletown also recruited students from its National Academy Bio-Med program to monitor the system from the sidelines. These are students in the school’s STEM program and sports medicine club, who serve as sideline assistants during the season. When certain thresholds occur, they will deliver their finding to Olejniczak, the district’s athletic trainer. In turn, he analyzes the data for further action, which could include a referral to the team doctor, who specializes in concussion injuries and management.

Last season 100 percent of Middletown’s varsity football players wore the mouthguards in games, but Rhodes says it’s imperative that the mouthguards are tested during practices, too.

“This is definitely a situation where you don’t really learn until you’re on the field,” says Rhodes. “It’s almost impossible to replicate what the devices go through in your lab or office. You can’t put helmets on engineers and have them run around and hit each other. We need a real learning experience. You get the bigger hits during games, but the volume during practices.”

The material for the mouthguards, Vistamaxx, is made through a partnership with Exxon Mobil, and is a proprietary material that creates a more secure fit than traditional ones – and maintains it. It crystallizes slowly to make a tight dental impression and is hard to chew through as it is significantly more durable than other materials.

Rhodes says they were also able to design a product that can work on athletes from age 10 to adulthood. The sensors turn on when they’re in an athlete’s mouth and off when they’re not, or when they’re dropped. But Rhodes cautions that the technology isn’t perfect, and that false positives are possible.

“But we’ve improved by leaps and bounds,” he says. “We can tell when a mouthguard gets knocked out, vs. when a player lets go of it or throws it somewhere. This tool gives a team visibility on what’s really going on, and an ability to pay closer attention and look harder at symptoms.”

At Mt. Zion High School in Illinois, 45 minutes west of Champaign, athletic trainer Dustin Fink values the mouthguards for the information they give him.

“I was skeptical at first of any sensor technology,” says Fink, who also runs The Concussion Blog, through which i1Biometrics reached out to him. Both the mouthguards and the blog came out in 2010. “I didn’t feel like anything could replace what I do as an athletic trainer and healthcare professional. But if there was going to be a sensor, this made sense, as something in the center of the mass of the head, not connected to the helmet. It was the only sensor I felt comfortable with, based upon my background and fact-checking.”

Sensors such as those embedded in the mouthguards deliver feedback athletic trainers, coaches and anyone monitoring physical performance can use, Fink says.

“A player can tell us they feel good, but if the data is telling us something different, then perhaps we have a reason to investigate further,” explains Fink, who’s been an athletic trainer since 2000. “When I first started out, a kid gets hit hard and maybe he sees stars, maybe he doesn’t. If he’s OK 15 minutes later, you let him back in. But now we’ve got this device, giving me feedback in terms of maybe what happened to the head during an impact, how many G’s they took. And really, more interesting to me, is the number of impacts they’re taking. Not every hit creates a concussion. Research has shown there’s a cumulative effect of hits, even low threshold ones. That’s my big reason for using it.”

As the sensor moves in space, the accelerometers are able to tell where the initial impact came from. Then they can use that model to create an image on the dashboard that corresponds to the location on the head.

Fink’s school used the sensors for their fall 2015 season.

“It was awesome. I worked with i1Biometrics to get as many as possible out to the kids. It was a symbiotic relationship. They wanted the data and the real-life experience of an athletic trainer using it,” he says. “I came in with a lot of skepticism, and I came out very impressed with what this can do and how it can help me.”

This made a big difference half-way through the season, Fink says.

“We started holding kids out of practice because they’d had too many hits the week before, as a preventative measure, so they have enough time to recover,” he says. “The other way it can help is for education.”

The coach started using the data to hone players’ techniques. For example, seeing a lot of force at the top of the helmet means they’re dropping their head, putting them at risk for spinal injury. They can also use Vector to investigate the hits that cause concussions, which vary from player to player. That could lead to adjusting thresholds that trigger when to pull players.

Players who were at first uneasy about information that could pull them from practices and games, came to appreciate the benching, which also helped them not to lose face in front of their peers, as staff deferred to the data.

“I’ve tried probably 20 or 30 different types of technology for concussions in football and other sports and there was nothing I had fallen in love with,” says Fink, who commended the customer service and easy set-up. “But I’ve fallen in love with this. It’s the first time I’ve ever done that.”

There’s more to come with the Vector, in that there will be a mid-season launch of video time sync. That means all of the video footage will be synchronized with the sensor data for review and application of coachable moments.

“These are products for athletes, by athletes,” says Harper, who has played football, coached and is a parent of players. “We understand the game.”

Top photo: Initially part of a pilot program, Middletown was the nation’s first high school to beta test i1 Biometrics Vector MouthGuard on the field. The Vector is now available for use in colleges and high-school programs nationwide. (Photo courtesy of i1Biomterics.)