“My life has given me a special lens for people marginalized by the intersection of race, gender, class, and disability.”

Growing up on the Southside of Chicago, Heather Dowdy found her relationship with her hardworking dad led her to develop products that everyone can use.

Heather Dowdy walks up the snowy steps to her father’s home—she’s returned for a visit to the South Side of Chicago where she was raised. She rings the doorbell, but after a few minutes with no answer, she takes out her smartphone to dial her dad’s number. As the phone rings, she’s feeling the change of how different things are now than when she was growing up—specifically, how technology has changed everything about the way she and her parents, who are Deaf, communicate.

Rewind to teenage Heather warming her numb hands in between ringing the doorbell and peeping through the rectangular window of glass in the door. She’s locked out. Annoyed with herself for forgetting her key before leaving for school that morning, she keeps pressing the doorbell because she’s hoping her dad will walk by the lamp that flashes each time it rings.

Half an hour has gone by. With no other way of getting in, she waits. She sits down on the steps and uses the waning afternoon light to crack open her new library book. Suddenly, the door opens, and her dad, Royce Martin, signs: “Did you forget your key again? Come in.”

*****

For the past 12 years, Heather has been going and going: college, marriage, three kids, quickly ascending in her career, and then pausing graduate school for a big move to Washington State to work at Microsoft on accessibility.

But today, she’s taking a moment to breathe and reflect. She’s back home with her dad, Royce. The two of them walk down their snowy, tree-lined street, and Royce can’t take his eyes off his grown daughter—he teases her, but he’s also beaming just to have her near. It’s hard that she lives so far away. There is a camera crew in his house, and he thinks it’s because his firstborn daughter is a big deal: an engineer working on accessibility at Microsoft.

However, it’s Heather that’s there to shine the light on how he helped guide her to meaningful work, how he instilled this incessant hope that if she pushed herself, she could do anything, and to reflect on how it’s really her dad that’s the big deal.

In fact, it’s hard to tell who is more proud of whom.

*****

Royce lost his hearing during birth, and Heather’s mother lost her hearing as a toddler due to a childhood illness. Her parents met in college through mutual friends—all of whom were part of a deeply connected African American Deaf community. Heather came to know these folks as family as she attended weekly social get-togethers, church services, and other community events with her parents.

“People sometimes don’t realize how social and talkative the Deaf community can be,” Heather said. “Those events would last ages.”

As a young girl, tired and bored, Heather would yank on her dad’s shirt, signing “can we please go?”—an action so frequent that it became her sign name. Instead of signing each letter of a person’s name, people can be given a sign name—a nickname. Heather’s is the sign for the letter H that moves up and down as in the sign for “hurry.”

Royce balanced that social life with a decades-long career for the postal service, working primarily at night.

“What I love most about my dad is how he believed in working hard for our family. He was such a hard worker,” she said, her voice quivering with pride. “I would see him tirelessly go to work, rarely missing days.”

This kind of “grit,” Heather says, is what living on the South Side engenders in its residents. “Some people say nothing good comes from the South Side of Chicago, but Michelle Obama did. And I did too.” Saying that you are from the South Side is a badge of honor, she explains.

Heather: “I can’t wait to see what you have to say once this is posted.”

Royce: “Oh really?”

“It means that you’ve come through rough spots. But, it also means that you’ve got a sense of pride, and that comes with the heritage that is the South Side of Chicago.”

Heather’s home on the South Side neighbored those of other black middle-class families, which Heather chalks up to decades of housing discrimination that left most of the area segregated. As a result, neighbors came together as family—like the community of African American Deaf people in which the Martins were deeply ingrained.

*****

The Martin family moved to this home in 1993 when Heather was a girl, with a younger brother and a new baby sister on the way. A shooting in their previous neighborhood had tragically killed an eight-year-old boy, a friend of the family who was the same age as Heather’s brother. Royce’s unwavering work ethic and financial prowess enabled him to relocate his wife and children to this new neighborhood, where they were one of the first black families on the street. Heather remembers a few white boys trying to intimidate her and her brother, saying to her that their families were members of the Ku Klux Klan. But the South Sider held her head up high and ignored them . . . with style, she might add.

“Thriving when you don’t have everything you need, plus looking good while doing it,” she side-smiled, “no matter what they throw at you. We believe that no matter how little you think you have, you have more than enough to share with someone else. That’s the South Side.”

Giving his children a sense that they belonged was one of Royce’s driving priorities, hence regular social events with the Deaf community. Heather observed an added level of complexity faced by black people in the community and those who had a hard time with money; she wants to foster belonging by building technology that’s accessible and affordable for them.

“My life has given me a special lens for people marginalized by the intersection of race, gender, class, and disability. So now, I make sure I’m representing Chicago, my background, and people that look like me—but also people in my family like my parents that need to be empowered. I’m looking for the marginalized within the marginalized.”

Standing in the kitchen of her childhood home, Heather and Royce pose for a photo. Royce signs that Heather is the spitting image of her mother.

After the camera snaps, Heather walks over to the computer screen to peek at the shot, and suddenly she’s speechless, hand over her mouth; she’s moved to see her dad being honored in this way. He walks up behind her and plants a kiss on her cheek, then sits back down.

*****

Heather credits her voracious mind to her dad—a copious reader, a passion he passed on.

“When she was younger, I taught her how to read, and she would just stay in her room, reading,” signed Royce as Heather interpreted. “In maybe third to fifth grade, that’s when she fell in love with science.”

He said it was hard for her at first, but once she became fascinated by it, she was determined. She knew that she wanted to be some sort of inventor because she loved all the gadgets around her house: the lamp that flickered on and off when someone rang the doorbell, the vibrating alarm clock underneath her parents’ mattress, the text telephone (TTY—a display and a keyboard connected to a LAN line that contacts a third-party service that relays communications back and forth), and the video relay service equipment that her parents used to communicate by using American Sign Language (ASL) instead of typing, the TTY’s evolution.

But she didn’t know of anyone making those devices; it hadn’t occurred to her yet.

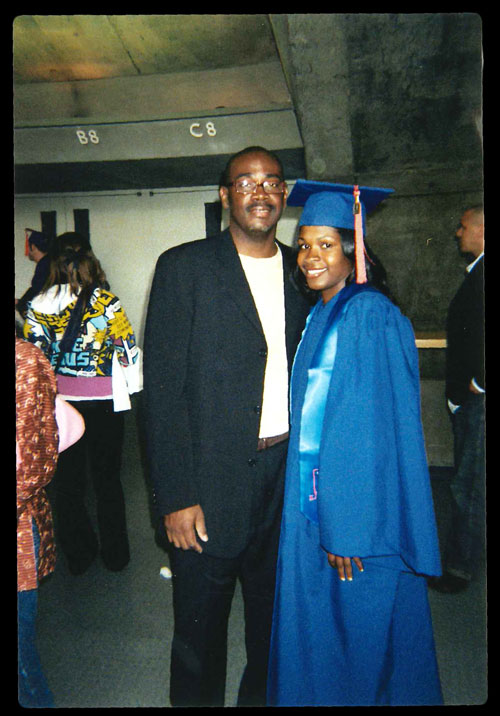

Heather and her father Royce celebrate Heather’s college graduation

from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

One day, young Heather came home from junior high school with an idea. She’d often toss out ideas to her father for what she could be when she grew up. Back then, he was endearingly tough to please, she remembered. Not in an unloving way, but in a way that emboldened Heather to challenge herself.

Her dad was reading in his tattered, gray arm chair. She touched his arm gently and signed, “Dad! What if I become a sign-language interpreter?”

He peered at her over his book, set it down, and signed, “No.”

“What? I thought you’d be excited. I’ve been interpreting for you and mom my whole life,” she pressed. “Why not?”

“Too safe for you,” said Royce. “Believe in yourself. Do what makes you uncomfortable.”

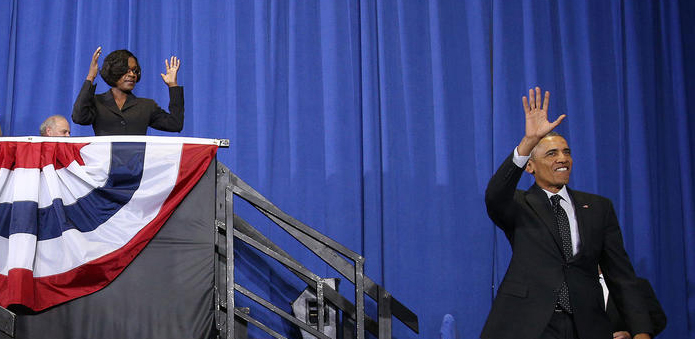

While Heather walked out of the room thinking that it was strange that he wouldn’t want her to choose interpreting as a career, she knew that he was right. So even though she interpreted for then-president Barack Obama during a 2015 national monument dedication in Chicago, she respected his commitment to working hard for the sake of the family. So, she would keep looking for something that challenged her.

*****

After her sophomore year of high school, Heather went to a summer engineering program at Chicago State University. There, she got to dig in to the hardware of all the gadgets that she loved. As she soldered the circuit board for a phone, she thought about how so many people who have hearing loss, at that time, couldn’t use the phone easily—the feedback on hearing aid devices made people on the other end of the line sound like they were in a construction zone. “Wow, I could make accessible technology and really change people’s lives.”

“Today, I never take it for granted that I can send my dad a text if he doesn’t see me standing at the door. The world of pagers and mobile phones really changed our world,” Heather said.

It turns out that there was a name for being an inventor of technology for people who are Deaf or hard-of-hearing. She came home that summer and told her dad, “Engineer. I’m going to be an engineer.” At that point, Heather had never heard of any female, black engineers. Surely that qualified as uncomfortable.

Royce said nothing, his kind eyes narrowing in on hers. He smirked, shrugged, and then walked down the narrow hallway to rest up for the evening’s shift at the post office.

*****

Heather fought to earn a degree in electrical engineering. Although she was told by a dean that she would never become an engineer after just glancing at her, she stayed motivated to continue because this wasn’t just about her—she knew that she was working to serve others. She was going to bat for people like her parents.

“I just remembered my daddy,” Heather said, tearing up. “How he has worked for nearly 40 years at the post office and never complained. How he pushed me to not fall into something easy just because it was easy. He kept me going.” Royce empowered Heather to challenge herself so that she, in turn, could challenge the field of accessible technology. Heather earned an internship and was hired to improve how mobile phones work for people who use hearing aids.

“I saw how mobile phones and pagers changed the world for people like my parents, who were Deaf, and for children of Deaf adults, like me,” she said. “I was hooked.”

“I didn’t expect her to stick with engineering,” Royce signed. “I thought she would turn out okay, but wow, she really stuck on the path and became successful. I’m so proud of her.”

“Okay?” Heather signs back to her dad. “Just okay?!” They both laugh.

Heather interpreting for then President Barack Obama

during a 2015 national monument dedication in Chicago.

Heather now leads the AI for Accessibility program at Microsoft that funds entrepreneurs and startups rooted in the disability community who are making use of artificial intelligence in the creation of accessible technology. She finds herself challenged every day, as this is not easy work.

“That’s why I like accessibility. We go to the most complex problem first. If we’re focusing on developing Cortana for students who have speech disabilities, can you imagine how much better it will be for you and me? Or for somebody who has an accent? If we can figure that out, then we make it better for everybody.”

Many of her life experiences taught Heather to look for people on the outside, for people who might feel excluded.

“Now, I make sure that wherever I am—a meeting, a boardroom, a school—I’m looking around for the person who isn’t speaking up or keeps getting cut off. I use my power that I am so blessed with to help find a way to include them.”

Heather is in a unique position to elevate good ideas for accessible technology, but she’s also advocating for people who need this tech but who might be overlooked because of their race, their socioeconomic background, their gender, or a disability.

“If I can just remember every day that there are people who didn’t go to college, who don’t have degrees or the earning power to buy the technology we make, then I can push myself and the engineering team to do better.”

“We are smart enough to take on that challenge,” she said, a refrain borrowed from her father. “We can do more than we think.”

*****

Photography by Sarah Matheson. Videography by Seth Rice. Additional reporting by Amanda Finney.