“It’s important to have people in your life that show you that success is real.”

Teacher and renowned New Orleans artist Richard Thomas set an example that inspired a teenaged Howard Robinson to take risks and see a future filled with more.

Chatting beneath the sign for Gene’s Po Boys, a bubble-gum pink stucco building on the corner of Elysian Fields Avenue and St. Claude Avenue in New Orleans, two men 30 years apart in age lob names back and forth to spark their memories: former principals, choir teachers, classmates. “Remember her?” “Oh yeah, I knew her cousin. Remember him?” “No, what year did he graduate?”

Formerly an art teacher at McDonogh 35 High School (“35”) located in the Seventh Ward, Richard Thomas can’t exactly place graduate Howard Robinson—hundreds of kids have come in and out of Mr. Thomas’s art studio/neighborhood hangout over the years. It doesn’t seem to bother Howard that the now-famous New Orleans painter doesn’t seem to remember him.

“It didn’t really feel like you were trying to be a mentor or come across as ‘Son, here’s what I learned when I was your age,'” Howard said to Mr. Thomas. “It felt just more like, hey this is a person who’s trying to help kids figure out what they want to do by sharing what he does.”

Howard, who now lives in Seattle, is home visiting his mom. But today, he’s spending the afternoon wandering the neighborhood, reminiscing with the man that he recently identified as a defining figure in his life.

After lunch, the two men meander toward their next destination, a 100-year-old historic brick building on St. Claude Street—Mr. Thomas’s art studio and storefront. Mr. Thomas was an art teacher, but he also ran his own art business. When he bought the studio in 1992, Mr. Thomas had the vision for the space; he’d make and sell his artwork there, but it would also be a place for neighborhood youth and students, like Howard, to hang out.

As a teenager, Howard was a bright student. His mother, family, and friends all watched out for him, but it didn’t change the reality that he had few older male role models in his life. (In fact, it wasn’t until his first year at “35” that he’d had a teacher who was black and male.) Although the circumstance wasn’t unusual, something in him was curious if his path could be different, but Howard couldn’t easily see how.

“Growing up, many people pushed for black and successful to mean being a rapper or a football player,” he said. “I just didn’t want that for me.”

Being in Mr. Thomas’s studio would change that for the teenager, by just having somewhere to go after school.

Those moments would define him though he wouldn’t realize it until later—having a role model who provided a welcoming place to go during his formative years.

*****

With students under his wing for decades, Mr. Thomas is almost an institution in New Orleans—an artist and activist who captures and preserves New Orleans’ culture through his paintings. Last year marked 40 years as a celebrated and featured artist for the annual New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival—where he creates and sells portraits of iconic jazz musicians, such as Louis Armstrong, Ernie K-Doe, and Fats Domino, all appearing in vivid blues, greens, and pinks. Much of Mr. Thomas’s work garners thousands of dollars, and he’s met and painted portraits of celebrities like Lena Horne and Redd Foxx.

During Howard’s sophomore year, his friends who were enrolled in Mr. Thomas’s art class were invited to the studio to finish a final project. Since the studio was just blocks from school and he didn’t have anywhere to be, Howard tagged along. They left through the crumbling concrete courtyard (the historically prestigious high school was showing its 70-plus years) and headed south on Columbus Street. (Notably, McDonogh 35 was the first public high school built initially for African Americans in the state of Louisiana, in 1917.)

The boys pushed open the door to the studio, untucking their mandatory school uniforms. Looking around, Howard saw several teens silk screening or drawing or painting at a big work table. Brushes, paints, tools, prints, and posters were all in a state of creative chaos, the smell of ink mixing with the humid Louisiana air wafting in through the open windows. Mr. Thomas was there working on a massive order of his Jazz Fest prints that had been commissioned for national resale, and his mom, the gallery manager, sat at the front counter, a kind of mother hen to the whole place.

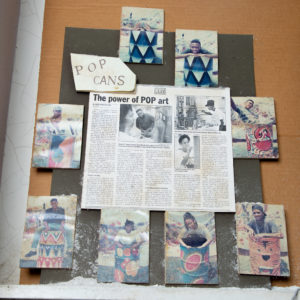

Sporting his famous flat top, Richard Thomas garnered attention in a

Sporting his famous flat top, Richard Thomas garnered attention in a

local newspaper for his mentoring project, Pieces of Power.

A group of kids that Howard usually saw hanging out at the corner store waiting for the bus after school were making noise upstairs. He looked up and saw a second-story loft. Walking up the creaking white stairs with its black wrought-iron railing, Howard spotted a worn-in green couch taken up with a few neighborhood kids playing Madden.

“A’ight, let’s go,” he thought as he dropped his backpack and flopped down, reaching for a free controller. If nothing else, he could save the quarters that he usually spent at the arcade.

*****

For the next three years, Howard observed Mr. Thomas welcoming in more and more students from the neighborhood, not just the school. He offered them and Howard the chance to make some money working at Jazz Fest selling his posters. Howard noticed the way that Mr. Thomas ran his business, how he built his network of agencies and politicians and musicians, and how he hired employees of his own to help to fill orders.

“I saw that he didn’t just print up 5,000 posters by himself. He had other people and his own company that ensured he was set up right to get what was due for the work,” Howard said.

Everyone adds to your understanding of what success looks like, he continued. “So here’s this guy who looks like me, is from my same city, and who owns his own company. I began to believe that success was possible for me, that it wasn’t some random thing.”

Up to that point, Howard, like many kids in high school, didn’t have a clear picture of the future. But after meeting Mr. Thomas, a new vision inched its way into his sights, and he found himself dreaming of a future with more success than he’d thought possible before.

*****

New Orleans feels a lot different now than in the 1990s, Howard remarks to Mr. Thomas, as they stand in the drafty studio, both checking out the mural that Mr. Thomas was painting just as Hurricane Katrina hit. The two exchange worries about how gentrification might dilute the story of their unique, culturally rich hometown; it’s a post-Katrina world, and nothing will ever be the same.

Especially Mr. Thomas’s hair, they laugh. Instead of the famous flat top that Mr. Thomas used to sport (a retro move for him even then), Mr. Thomas now has waist-length dreadlocks. “Katrina made me get the dreadlocks, man,” Mr. Thomas tells Howard. “I couldn’t find nobody that could cut my hair.”

Hurricane Katrina also changed the way that Mr. Thomas did business. Before, he wouldn’t negotiate the price of a piece of artwork. His prices were his prices. Now, he works with local buyers, sympathetic to the way that the hurricane tore through the city’s economy.

Mr. Thomas’s studio took a hit too. The room was flooded with water, which destroyed all the work on the ground or leaning up against the walls. “You think I would have learned my lesson,” Mr. Thomas remarks as he picks up a print from the floor that’s leaning against the wall. Howard sifts through canvases as Mr. Thomas regales him with stories of how he became an artist.

*****

Mr. Thomas’s career started in college, when he started painting about social issues and the experience of being African American living in America. It was his way of demonstrating, because he was too young to join the civil rights protests in the 1960s.

“I was about eight or nine years old, and I remember going to those meetings. I remember when Klans tried to run me and my brother off the street in Bogalusa, so our parents wouldn’t let us protest.

My freshman year of college, I was in a Black Studies and Black Philosophy class. I realized that there was so much I did not know, that hadn’t been taught to me,” he says.

After a politically radical few decades, he settled in New Orleans and began to focus on the local culture and helping kids find a way to express their own political emotions through art—or, like in Howard’s case, give them somewhere safe to hang out.

Howard left the familiarity of Mr. Thomas’s art studio behind when he graduated high school in 1999, went to college, and eventually landed at Microsoft. He now volunteers both with Team Rubicon, a disaster-relief nonprofit that helps clean up or rebuild or rescue, and Year Up, an organization that provides underserved and minority young adults with internships in technology and gets them into the workforce or on track to a college program in one year. Howard mentors the Year Up interns who work at Microsoft.

Though he may not be an artist or have a studio space in the middle of a city, Howard uses these programs to offer up himself as that welcoming space.

And now, he has come full circle as a patron of Mr. Thomas’s art. They stand in the studio, negotiating a piece that’s caught Howard’s eye: a color-saturated portrait of Mahalia Jackson, the New Orleans-born “Queen of Gospel.”

“How about $200,” Howard starts.

“I wanted to sell both of these together,” Mr. Thomas counters, gesturing to another piece. “But make me an offer.”

Howard’s eyes twinkle, “Yeah, let me think about it.”

“Yeah, no, it’s okay. Look, you don’t know how good it feels to get someone coming back after all these years to buy my stuff. If all the kids did that, I would be doing okay, you know,” he laughs.

“But just so you know,” Mr. Thomas adds with a grin, “I can make you a deal on that.”

*****

Photography and videography by Kendal Thomas. The New Orleans mural featured in some videos for this story is by Seattle-based artist, Craig Cundiff. Additional reporting by Amanda Finney.